How to Guard an Author's Voice While Editing

And how, as a writer, you can guard your own voice

With our voices, we may sing or shout. Our voice is our power. Anything that threatens to dampen our voice is antithetical to our full expression, and hence to our vitality and our process of self-actualization.

I've referred to an author's "thumbprint" here—that's another way of saying "voice."

It's the lexicon, style, tropes, and meter, plus an author's expertise and credibility in their field, plus the chosen P.O.V., plus the chronology and pacing they choose. There are micro and macro elements of voice.

Voice is the core of an author's ORIGINALITY, which is as valuable to the writer as a patented idea is to an inventor.

It's a felt sense, but has subtle algorithms scaffolding it.

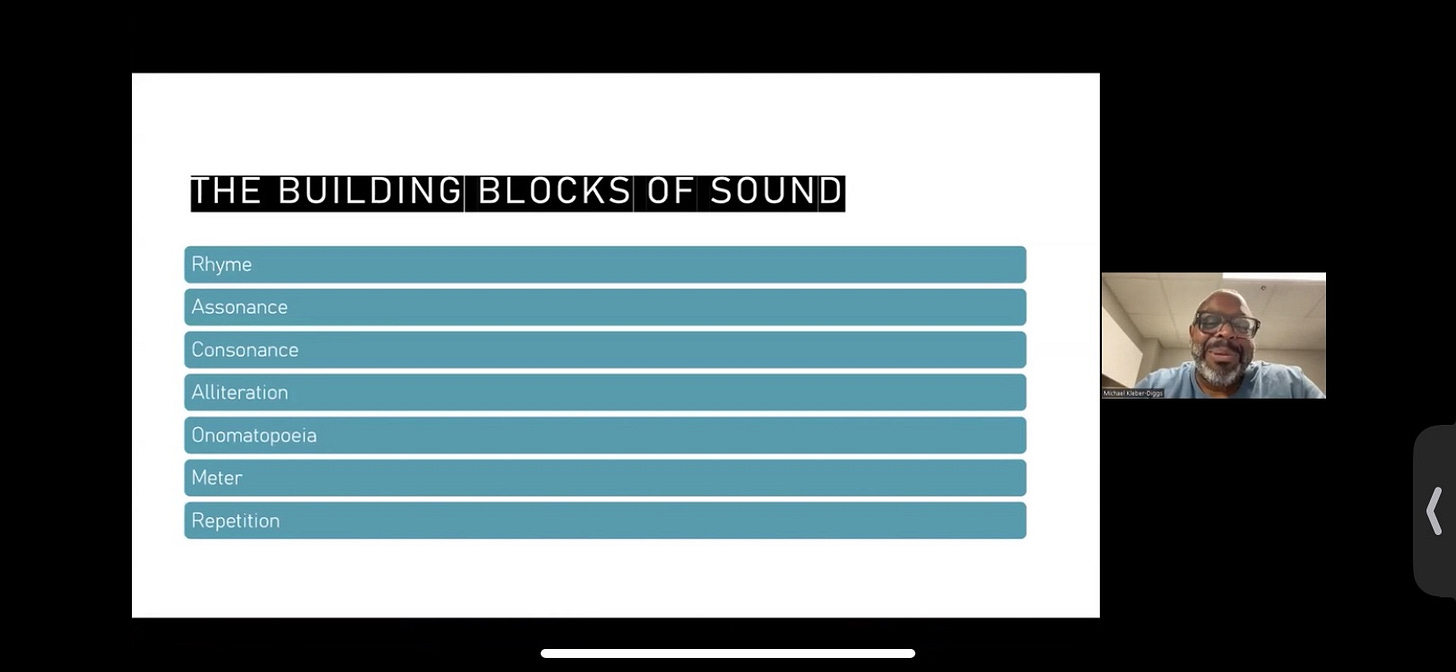

I recently attended a webinar called "The Art & Craft of Sound in Creative Writing" offered by Authors Publish and featuring Michael Kleber-Diggs. All the tropes he covered (rhyme, assonance, consonance, alliteration, onomatopoeia, meter, repetition) partly define voice. I'd add punctuation and other devices mentioned here.

As writers, some of these we use consciously, and some are unconscious but still characteristic of our style.

I think that the more conscious of rhetorical devices a writer and an editor are, the more capable they are of recognizing what constitutes voice, and the more successful they'll be at shaping and maintaining a unique and consistent voice, so that it functions a lot like one's personal brand. An author must decide if a suggested addition or change is in alignment with their "brand"—or perhaps they've hired an editor to improve their brand.

"Sound can shape the mission of a project," said Michael Kleber-Diggs. He read "The Mosquito" by Brian Turner out loud to demonstrate one writer's mastery of the devices.

Punctuation shapes sound. As a writer, I am very intentional and creative with punctuation. I rely on it the way a musician relies on musical notation, rest notes, and metered notes to compose. (Don't be afraid to use the semicolon!) Word choice with sound being the primary driver is a different process than word choice without consideration for the resulting sound or meter, assonance/alliteration/consonance, and so forth.

Editing poetry requires particular tenderness or delicacy because the writer has been so intentional about their choices. Michael said, "Stand-up comedy and poetry are very similar. It's all about pause and space. In poetry, we have the volta, which is the pivot in the poem, and in stand-up comedy it's the punchline."

Have someone read what you've written out loud. I was a regular at a writing workshop in New Rochelle where this was the mode, and it took some getting used to, but it's an effective way to hear where your words might trip a reader up, or just see if you like what you wrote when the tables are turned and you're the listener. Of course, reading your own work aloud is something I always recommend. It's about breath control. Sometimes you may underpunctuate, leaving out commas and periods to create a sense of urgency or chaos.

Think about how your work will be read by others, in their inner voice. Caesura, usually referring to carefully considered line breaks in poetry, can also be applied to paragraph breaks in a story, or chapter breaks in a book. A whole piece has rhythm, not just each sentence, and pauses can be a storytelling device. As an editor, I'm often rebreaking paragraphs for better effect. So many elements contribute to the flow of written work; the first draft can be splatterpainted intuitively, but revisions are typically necessary to hone the artwork. Aren't we lucky that our clay doesn't dry instantly, and we can continue refining until we decide it's debut time?

If you want to find a good editor, ask them to talk about what they love about the craft of writing. Read what they've written. Speak with their past clients to be sure they felt their voice was held sacred during the revision process.

I guard authors’ voices preciously, even as I suggest cuts, offer language from my imagination, and rearrange. I polled some recent clients with this question:

What is “author voice”? And, how did I (or how does any editor) revise thoroughly… and still conserve the author’s voice?

David F. wrote: “The author's voice emerges from each author's unique flow state—where the author's subconscious perceptions and emotions merge with words and imagery collected over the course of a lifetime. An authentic author's voice should demonstrate a sense of stylistic consistency, which evokes those words and images from the flow state. A great editor (like Michelle) is able to tap into the author's flow state—essentially entering into the author's subconscious—and to propose changes from within that realm, rather than from her or his own modes of thinking.”

I think he nailed it. Some would call it empathy. I think my experience as a Tisch-trained actor comes into play. I embody not just the narrator but the characters, while considering the author’s intended audience and drawing on my familiarity with the publishing industry and current market trends at the same time, to hone the material.

Sarah R. wrote, “I think the clearest definition of an author's voice is that when you read something you recognize who it is—like a painter's style or a filmmaker's style—you know a Coen Brothers movie when you watch it.”

She added some ways an editor can guard an author’s voice: 1) Asking questions—this invites the writer to consider a change and allows them to make the decision whether to alter the content, 2) Suggesting changes that do not alter the original meaning, and 3) Telling the author what you are taking away from the passage, and asking, ‘Is this what you meant to do?’

Sarah is a client-facing creative strategist and researcher. When advising clients, she always goes back to the agreed-upon strategy, and asks, “Does the work meet the strategic brief? Does it communicate what you are trying to communicate?” She said focusing on the objective empowers her to give meaningful feedback. She wrote, “I think the same is true with an editor. You've been asked to make a piece of work the author has written to tell the story they want to tell better. Stronger. You will always be respecting their voice if all the comments, edits, and changes you make are done with that as the end goal.”

Max J. wrote, “The author may use certain key phrases or have ways of expressing thoughts that is characteristic of that person, perhaps based on age, nationality, education, experiences, and interests. All this together creates the author’s voice. The author’s voice may change depending on the character being portrayed. A single author may have multiple personalities or voices.

“Editing may be limited to checking spelling or grammar. However, a thorough editor may legitimately demand much more, even a rewrite. A fortunate writer might find an editor like Michelle Levy, whose work is all-encompassing, with suggestions for sentence structure, word avoidance and replacement, paragraph division, plot cohesiveness, paragraph placement, and stylistic changes. Through all this, listening to the author-voice that sings in the mind allows the rhythm and cadence to remain compatible with the originator of the work, while improving the writing.” Max said he values an editor’s “listening ear.”

Revision is an intense and laborious process. This is why polishing and publishing a book is such a grand and respectable accomplishment.

I’d love to hear from writers and editors. What is your definition of “voice”? How have you experienced the revision process? Did editors keep your voice intact? I know writers who’ve had the humor, sass, or verve stripped from their writing prior to publication; but most, I hope, will have encountered editors who tightened their prose, helped them clarify their message for readers, and left them with new and improved writing skills while honoring their authentic voice.

There is no fifth chakra (expression) without the fourth chakra (heart.)